For those of us in the UX design and design research industries, having a client ask for “focus groups”––or seeing focus groups listed in Requests for Proposals––are major pet peeves.

The title of this blog might be making a bold statement, but there are many science-backed studies showing why Focus Groups can provide skewed results, and why they probably are not the best tool for gathering customer feedback or insights that are meant to inform product and service decisions. Design and UX research methods like in-depth interviews, observations, and co-design workshops are much more effective for gathering unbiased feedback and getting at the underlying motivations and needs of users and customers.

What are focus groups?

In the traditional sense, a focus group is a small group interview or guided discussion about a particular product or service (or political message, TV series, the list goes on…) to gather feedback. Most frequently used in a market research context, focus groups generally include a moderator and six or more participants matching a target audience who come together in one room to discuss a specific subject, give opinions, feedback, and feelings, and in some cases, generate new ideas for products, services, or features.

Recruitment for focus groups usually involves many of the same types of efforts used to recruit for design research, such as identifying key user groups based on various demographics, socioeconomic factors, and behavioural characteristics, as well as using screening questionnaires, emails, social media, and phone calls to find the right participants for the research activity.

How do focus groups differ from other design research methods?

Workshops vs. Focus Groups

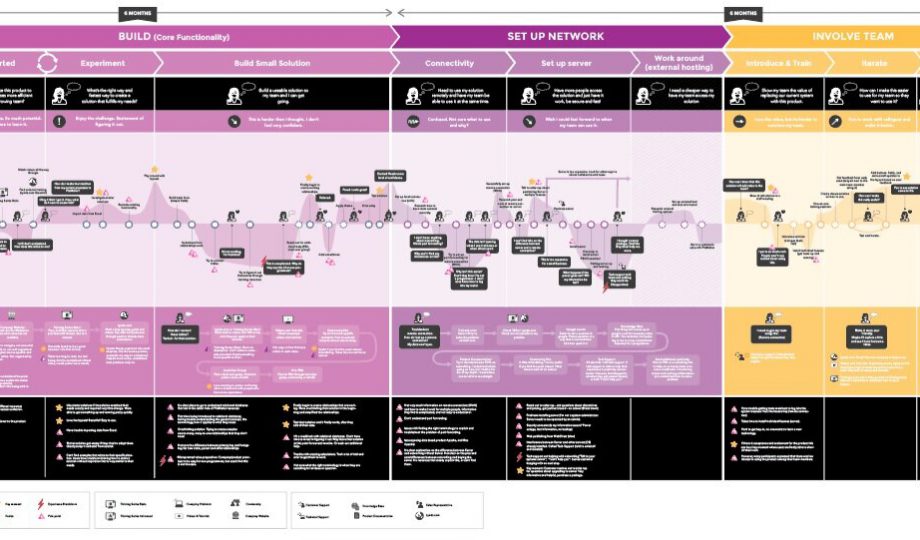

A co-design workshop (or really any workshop) is similar to a focus group in that it gathers a set of participants together in a room (virtually or in-person) to converse about a specific topic. In general, however, workshops are much more collaborative and participatory in nature. Instead of having 10 people sitting in a circle around a moderator and answering questions or providing their opinions (as focus groups do), workshop participants usually work in teams and engage in exercises and activities to create something. This might be a customer journey map, or maybe teams are simply working together to generate solutions to a problem. Workshops are much more creative and action-oriented. (And if this style of workshop sounds like what you are doing in your focus groups, then….you might actually be holding a workshop or “design jam”).

Interviews vs. Focus Groups

Interviews––including in-depth and semi-structured interviews used in design research––should always be conducted one-on-one with individuals, whereas a focus group will have upwards of 10 people in the same room at the same time. Interviews typically involve an interviewer and an interviewee (the research participant), and an interview protocol and script to guide the line of questioning. They can be conducted over the phone or in-person (which are known as “contextual” interviews).

While focus groups tend to include more back-and-forth conversation (which is where many biases tend to sneak in), interviews are much more about listening. A skilled interviewer will ask pertinent questions and know when to probe deeper––but they should never interject their own opinions or feelings into the session. Their job is to listen to the participant and ask questions to get at deeper motivations and feelings. In the way that focus groups are structured, even if the moderator does not interject with their opinions, other participants will. This can lead to serious issues when it comes time to validate the research findings (read more on this below!)

Reasons to stop using focus groups

There are many human tendencies based in behavioural psychology and sociology that make focus groups problematic tools for uncovering “unbiased” opinions and insights. These biases and human behaviours are entirely natural, but they can really complicate user research. Seven effects that are particularly dangerous for focus groups include:

-

Groupthink. A well-documented psychological phenomenon, groupthink occurs when a group of individuals set aside personal beliefs and opinions in order to reach consensus––and, as Psychology Today points out, this often involves the individuals making “irrational and non-optimal decisions” as a group. This behaviour can be linked to a desire to conform, or a desire to uphold harmony among group members.

-

One classic example of groupthink (in a focus group setting) is when a moderator asks a question, and one person immediately gives what sounds like a good answer. Then, the rest of the group simply agrees without adding their own input. The moderator may try to push the discussion forward, but all group members merely mirror what the first person said. This might come from a desire to conform, or a desire to “not rock the boat”. Either way, this is groupthink in action.

-

-

Introversion. There are extroverts, there are introverts, and there are folks who straddle the line between both personality types. In general, introverts are more quiet, reserved, and thoughtful individuals. Complex social engagements can be draining for them. In a focus group setting, an introverted participant may not feel comfortable interrupting a group of people to give their thoughts, despite the fact that they, too, have valuable opinions to add to the discussion. In the groupthink example above, an introvert would be much less likely to share their thoughts and feelings, which results in their input being pushed aside, ignored, or remaining entirely unspoken.

-

A tendency to lie. Similar to groupthink, focus group participants may flat out lie about a subject because they do not want to deviate from the opinions of the group. In a worst case scenario, a participant may give untrue answers simply because they don’t really care about the topic (and/or might be in the session merely to collect the money/incentive).

-

Design research methods (like workshops and in-depth interviews) guard against this in a few ways. For example, people are much less likely to sign up for a 60-minute, one-on-one interview about a topic they do not care about, or which they plan to lie about. In an interview setting, there is really nowhere to hide, and no other person’s opinions to piggy-back off. As a result, a research team is much more likely to gather valuable insights from 20 in-depth interviews than 20 focus groups. Interviews also enable researchers to weigh responses evenly after the fact. In other words, if one interview participant has a negative experience with a service, but the majority of others reported positive experiences, these experiences can all be weighed in relation to each other. In a focus group, if one passionate participant reports on their overwhelmingly negative experience with a product, the moderator is more likely to hear biased or untrue opinions/feelings from the other participants, who are seeking to conform or exaggerating their own experiences to match.

-

-

Anchoring. This is a cognitive bias wherein a person tends to be highly influenced (“anchored”) by the first pieces of information they learn about something, which influences their subsequent decision-making. Anchoring bias can take hold in group contexts, as well. For example, if one participant speaks up to answer a moderator’s first question and provides a plausible fact or anecdote to back up their opinion, the remaining group members might “anchor” their own thoughts and feelings in that fact or story, whether it’s true or false.

-

False consensus effect. This is another cognitive bias in which a person assumes that they are “the norm”, and that their beliefs, actions, and personal qualities are relatively widespread throughout a group or population. In a focus group setting, this might mean that one person speaks up and gives loud opinions that they assume are held by the other group members as well, particularly if participants are from the same demographic. The false consensus effect can stop an introvert in their tracks, and can also lead to groupthink and a desire to conform among members who are too shy to disagree.

-

Loss of Focus. In general, with more people and opinions in a room, there is a higher likelihood that a conversation will derail and fly off topic. We’ve all experienced this before in the context of a work meeting, for example. In a focus group, particularly if there are stronger personalities present (who assume they are speaking for the entire group… false consensus alert!), it’s very likely that the discussion will get off track over… and over again. Of course a gifted moderator can help steer the conversation back, but not all focus groups are led by seasoned moderators with this ability. This sometimes means that moderating a group with a few passionate participants might feel like herding cats.

-

Domination. Honestly, this issue lies at the heart of many of the biases and effects listed above. Inevitably, in a group of 10 or more participants who are being asked to give their opinions and feelings, there might be one person (or topic) that continues to dominate the conversation again and again. This can lead to a loss of focus among other participants, groupthink, and the tendency to lie or conform.

Some of the behaviours and biases listed above might seem obvious, and you may be asking yourself WHY, if these effects are so widely studied by psychologists and sociologists, are so many companies and organizations continuing to use focus groups?

Simply put, focus groups are an effective method for answering a question quickly. Most focus groups strive to discuss/answer a very specific question, like “What are people’s feelings about gluten being used in snacks for children?” Companies are just looking for an answer, and the quickest and best answer that aligns with their pre-existing assumptions usually wins, particularly if money has already been spent to develop a new product or service. Focus groups will always result in an “answer”, and they will do so relatively quickly when 10 to 15 people are gathered into a room at once. This enables a company to say: “well, we did five focus group sessions that were each 90–120 minutes long, and we got the answers we were looking for from 50 people within a few hours.”

As this great blog post points out, “while a focus group methodology is supposed to explore the psychological needs of consumers, it may serve as much to fulfill the psychological needs of sellers.”

View this post on Instagram

Click through for more design workshop inspiration…

What should you use instead?

While we’ve highlighted all the reasons why you should not use focus groups, we still commend you for doing any form of user or customer research! You are already ahead of the game, when so many companies and organizations are not reaching out to get that feedback.

So what tools can you use instead of focus groups? Well, this depends on what you are hoping to find out, and why you are seeking feedback in the first place. Generally, we recommend using a mix of research methods to gather the most accurate and valuable insights. This might include conducting a survey and in-depth interviews, as well as holding a workshop with end users afterwards to validate the survey or interviews findings. Workshops are also great settings for having users ideate actual solutions to the problems and pain points identified in your user research.

Human-centered design and UX research methods are more likely to give your company the insights it needs to move products and services forward in an effective (and hopefully, money-making!) way.

Resources we like….

-

Psychology Today explores how groupthink works

-

Study in Quality & Quantity journal about the ethical challenges of focus groups

-

Focus groups shape what we buy — but how much do they really say about us?